Our Research Basis

Introduction: Our vision

We want to inspire hope in the lives of people affected by Functional Neurological Disorder, Multiple Sclerosis, and similar conditions by helping them get outdoors.

“E tūtakitaki ana ngā kapua o te rangi, kei runga te Māngrōa e kopae pū ana.”

“Though clouds may block the sky, the Milky Way is still behind it. Even the longest road has a turning, even the longest night has a morning.”

— Māori whakataukī

This whakataukī affirms that hope, like the wonder of the Milky Way, can always be found. Our purpose is to help people see beyond the clouds or the darkness and gain inspiration for their journey as they master whatever mountain they face.

At Mastering Mountains, we believe outdoor adventure uniquely and powerfully fosters the formation of hope. A life of adventure in the outdoors can feel far from reach for many people living with neurological conditions. That’s why we offer both group and individual mentoring and rehabilitation support to people diagnosed with Functional Neurological Disorder (FND), Multiple Sclerosis (MS), and similar neurological conditions, to empower them to overcome obstacles and accomplish a self-directed outdoor goal.

Through a personalised mentoring journey, connection to a like-minded community, and support with physical rehabilitation, participants can embark on an outdoor adventure that inspires hope in them and in others, particularly those affected by neurological conditions.

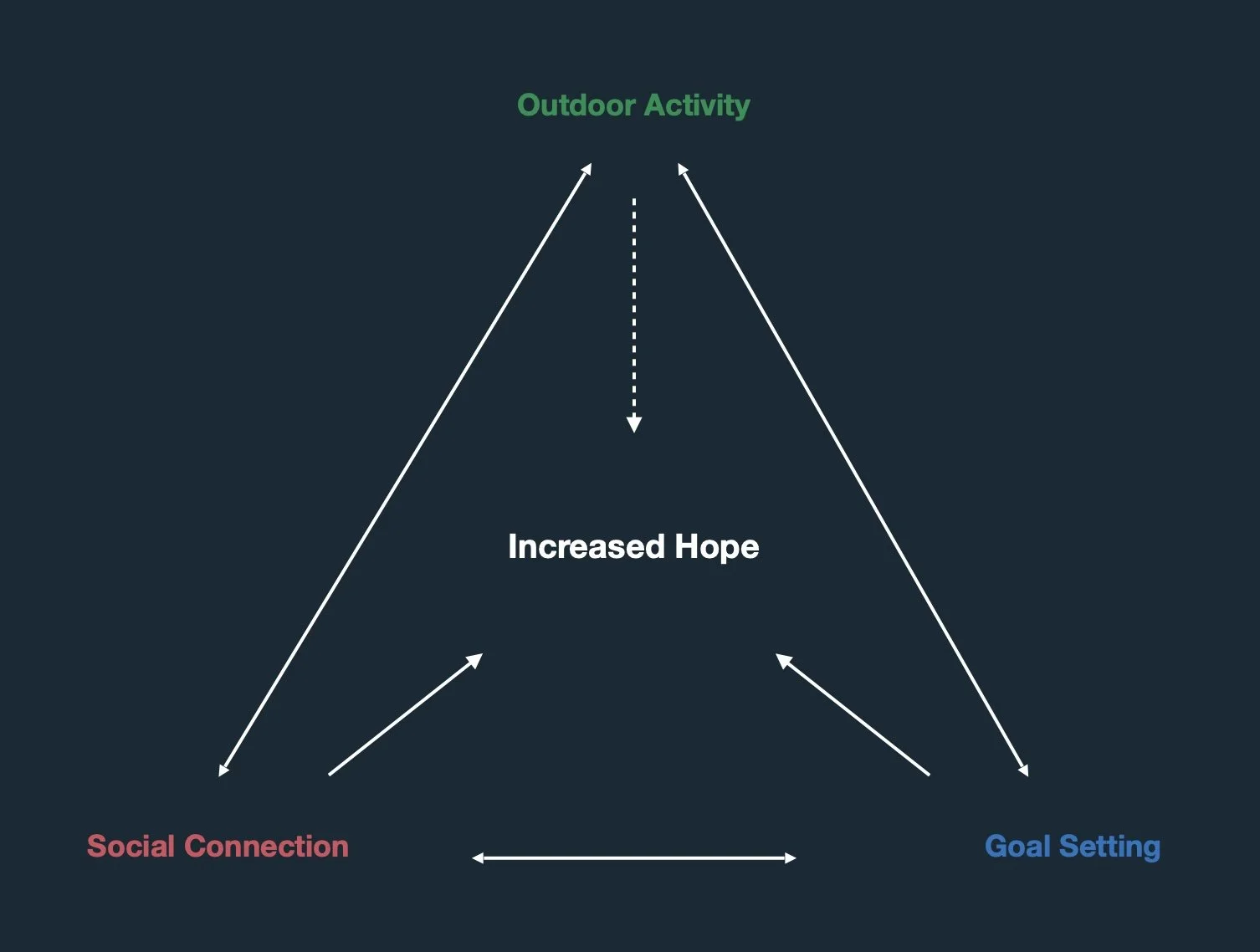

Our unique approach to cultivating hope in individuals with neurological conditions focuses on three key components: engaging in outdoor physical activity, fostering social connection and goal setting. These components interact with each other, powerfully increasing hope and other aspects of wellbeing.

While there currently does not appear to be any research investigating the development of hope in people with neurological conditions through a combination of outdoor physical activity, community and goal setting, parallel areas of research may offer some helpful insights.

Outdoor Activity

Our programme gets people outdoors. Programme participants select an outdoor adventure they want to achieve, and we provide the rehabilitation support, gear, safety equipment, and guidance needed to safely achieve that goal and maintain long-term access to the outdoors.

Green spaces are good

Growing evidence shows the meaningful, positive impact of natural environments on our brains and bodies (Williams, 2017), with “an inverse relationship between nature exposure and stress, both perceived and physiologic” (Shuda et al., 2020, Conclusion). Contact with natural environments has been shown to improve welllbeing, cognitive function and mood, while decreasing stress and lowering the probability of developing a host of chronic illnesses (Hunter et al., 2019; White et al., 2019; Berman et al., 2021). A German study found that nature-based therapy, when part of an integrated approach, can be an effective treatment for psychosomatic disorders (Joschko et al., 2023).

Exercise is good

Physical activity also has a positive impact on our brains, significantly enhancing neuroplasticity and cognitive function in neurodegenerative disorders (Ben Ezzdine, 2025). In a study comparing a group of athletes to non-athletes, physical activity was also shown to improve “cognitive functions, including memory, attention, perception, and mental flexibility … [in addition to] brain function, neuroplasticity, and nervous system changes” (Spytska, 2024, p. 8).

Green exercise is even better

Bringing together nature exposure and exercise, there is growing evidence indicating that “green exercise” offers greater health benefits than exercising indoors. Studies indicate that the psychological benefits of green exercise include improved mood, self-esteem, perceived health, sense of well-being, and cognitive performance (Gladwell et al. 2013; Shanahan et al., 2016).

Outdoor activity is enriched by social connection

In our programme, we find that in almost every instance, outdoor adventure improves social connection for our participants. There is growing evidence in the literature that outdoor activity promotes social connection. One review indicates that engaging in physical activity in a natural environment can enhance a person’s sense of social connection (Shanahan et al., 2016). A study of older adults showed that walking together outdoors helped mitigate social isolation, improving individual social wellbeing and a sense of belonging (Irvine et al., 2022). Related research by Motl et al. (2008) found that social support contributes to the positive relationship between physical activity and quality of life in people with MS.

Social Connection

Our programme participants gain access to a community of people who love to get outdoors, despite their neurological conditions. We host monthly support groups that enable programme participants to share knowledge and experience, and to walk alongside each other through the highs and lows of their rehabilitation journeys. We also strongly encourage programme participants to include others in their adventures, building stronger social connections with friends, family, and their local community.

Social connection improves health outcomes

Health research has established a strong relationship between social support and improved mental health and quality of life. Preliminary evidence shows that “social network size positively correlated with physical and mental health status in patients with FND” (Ospina et al., 2019, p.7). Likewise, Dhand et al. (2016) note that for people with neurological conditions, “having more friends beyond the caregiver is associated with health improvements and, complementarily, healthiness is associated with closer relationships among all people in the network” (p. 3). People who perceived themselves to be well supported reported better mental health-related quality of life (Schwartz & Frohner, 2005; Krokavcova et al., 2008) and tended to cope better with their illness (Rommer et al., 2016). These individuals also exhibited higher levels of hope and were more likely to be hopeful about the future, viewing themselves more positively (Foote et al., 1990, cited in Schwartz & Frohner, 2005).

There’s power in support from similar others

When giving programme feedback, it’s often peer support that our programme participants list as being a significant help in their journey with Mastering Mountains. This bears evidence in the literature. Thoits (1986; 2011) indicates that the best social support or assistance for coping comes from experientially similar others, in this case, others with neurological conditions who have successfully confronted the challenge they have faced (Krokavcova et al., 2008). Thoits (2011) suggests that this type of support has a significant impact on a person, helping “to shape the individual’s coping efforts, reducing situational demands and emotional reactions directly and perhaps indirectly augmenting his or her sense of control over life. Additionally, the sheer existence of peers who have coped effectively with the stressor generates hope” (p. 154).

Social connection enhances goal setting

In our experience, we have found that peer support enhances goal setting and facilitates progress toward goals. As suggested by Thoits (2011), this advice and empathetic understanding is invaluable, particularly in the context of striving toward the goal of a new and “desired ‘possible self’” (p. 155). Likewise, a study by Burke and Settles (2011) found “evidence that interacting socially with other goal-setters is associated with greater success” (p. 9) in the context of achieving a challenging goal.

Goal Setting

Our programme participants select meaningful outdoor adventure goals that challenge and inspire them. We use the rehabilitation journey as a means of developing the components of hope.

Goal setting works in connection with outdoor activity

In our experience at Mastering Mountains, outdoor adventures lend themselves naturally to goal setting. For individuals with neurological conditions who enjoy the outdoors, an anticipated exciting adventure can serve as a goal, offering a meaningful and inspiring objective that helps them maintain motivation throughout their lengthy rehabilitation journey.

Outdoor activities also enrich goal setting because the pathway to achievement is never straightforward, a context that provides an excellent opportunity for learning. The mentoring component of our programme often involves the mentor engaging with participants in solution-finding to circumvent or overcome the challenges they face on the way to achieving their goal. We engage in the process methodically as a means of learning ‘pathways thinking’ (Snyder, 1991) as a cognitive tool, so the person has the skills and agency to achieve future life and outdoor goals.

Goals can give us hope

Well-chosen goals can help us envision a better future and find hope. Tonnesen and Nielsen’s (2024) study examining physical rehabilitation in Parkinson’s patients reports that “rehabilitation goals could appear as stepping stones towards hope” (p. 20). Likewise, in the context of work with oncology patients, Von Roenn and von Gunten (2003) suggest that “working toward something reinforces hope” (p. 571), and that “most adults cope and sustain hope by making plans for the future, even if the future isn’t what they would want if they could choose” (p. 571).

Indeed, goals and goal achievement are foundational to Snyder’s (1991) conceptualisation of hope. His theory of hope can be summarised as:

“a dynamic motivational experience that is interactively derived from two distinct types of cognitive tools in the context of goal achievement–namely, pathways and agency thinking. His theory proposes that hope results from an individual’s perceived ability to develop numerous and flexible pathways toward their goals, allowing them to identify barriers and strategies to overcome these as they move toward goal achievement” (Colla et al., 2022, p. 3).

Furthermore, Madan and Pakenham (2014) state that “Hope may be fostered through identifying values and personally meaningful goals, defining them in clear measurable terms, and identifying multiple potential avenues through which goals can be attained” (n.p.).

Hope

The development of hope is an important focus area in our programme. Although engagement with hope as a construct rarely takes place explicitly, it permeates our approach as a foundational goal. We have chosen hope as a key indicator of wellbeing, not only because this connection is supported by the literature, but also because, in our experience, hope can have a profound impact on the lives of participants, their communities, and outside observers.

Hope as pathway and motivation

According to Snyder et al. (2002), hope contains two components: ‘pathways thinking’ and ‘agency thinking’ (Snyder et al., 2002, p. 258). Pathways thinking refers to one’s perceived ability to generate viable paths to reach a desired goal. Agency thinking refers to goal-oriented motivation and one’s perceived ability to progress along a pathway. In high-hope individuals, agentic thinking is evident in their positive self-talk (Snyder et al., 2002). Hope occurs when these two types of thinking come together, reflecting “the belief that one can find pathways to desired goals and become motivated to use those pathways” (Snyder et al., 2002, p. 257).

Hope is an indicator of wellbeing

Hope is helpful as an indicator of wellbeing across life domains. Broadly, research has shown that hope is a significant predictor of wellbeing outcomes and resilience across a range of populations (Joel Botor, 2019; Long et al., 2020). For example, hope functions as “an influential protective factor for mental health and wellbeing” (Colla et al., 2002, p. 5) that enables a person to cope with difficult life experiences. Conversely, studies also show an association between low levels of hope and depression and suicidality (Leite et al., 2019). In cancer patients, other studies have found that hope is an important psychological resource (Duggleby et al., 2012), which is “significantly correlated with quality of life in cancer patients” (Duggleby et al., 2013, p. 667), and may be associated with a decrease in symptoms and better functioning (Steffen et al., 2019). Murphy (2023) maintains that there is clear evidence supporting hope as a predictor of a “broad range of well-being outcomes including psychological well-being, social well-being, and subjective well-being” (n.p.).

Hope carries us through rehabilitation

Rehabilitation journeys are rarely without challenges, and in this context, hope is all the more useful. Hope is considered a “key attribute” (Soundy et al., 2011, p. 1) of those who successfully engaged in neurological rehabilitation. For example, Lee et al.’s study (2022) suggests that if a person with MS has hope while facing adversity, they may experience an increase in perseverance and passion for long-term goals, which may contribute to “enhanced coping resources and skills, which can ultimately result in better health, mental health, and rehabilitation outcomes” (p. 4). Snyder et al., (2002) point to research showing that high-hope individuals are more likely to “remain appropriately energized and focused on what they need to do in order to recuperate” (p. 265), while low-hope individuals are more likely to engage in cognitive pathways that increase anxiety and interfere with recovery. Similarly, the perceived importance of an exercise goal, combined with agency thinking and the perceived ability to achieve that goal, predicts goal achievement (Blythe et al., 2025). Without hope’s cognitive tools, a rehabilitative exercise goal could prove insurmountable.

Hope is social

However, it is important to note recent critiques of Snyder’s model of hope. Colla et al. (2002) explain that Snyder drew “a clear boundary around the individual” (p.8), focusing on internal resources while failing to adequately account for the “dynamic ecological system [that] encompasses the individual and many other layers of influence” (p. 8). On this basis, Colla et al. posit an expanded model of hope theory – one that includes “a sense of connectedness, or WePower, representing an individual’s ability to tap into resources within their social system” (p. 9).

Hope spreads

Time and time again, we’ve seen our programme participants inspire hope in others. Abrahamson (2024) observed that hope grows in community. Similarly, supportive relationships can be an important element of hope in elderly palliative patients (Duggleby & Wright, 2006). In addition to finding support to reimagine new pathways during hard times, Abrahamson (2024) quotes Dr Jacqueline Mattis, who suggests that community can provide “living examples of what hope looks like when it’s achieved”. In our experience, this is particularly important for individuals newly diagnosed, who often experience a loss of hope, both in their sense of agency and available pathways. Buoyed by a supportive community, the achievements of our participants often redefine their sense of possibility, inspiring hope in their families, their communities, and those observing their journey.

Our Outcomes

As As a result of their journey with Mastering Mountains, our programme participants see an increase in various wellbeing markers. For example, on average, our participants (n=5 | 2023-2025) experience the following:

28.2% increase in resilience, measured by the Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008);

38.6% increase in happiness, measured by the Pemberton Happiness Index (Hervás & Vázquez, 2013).

However, measures such as the Adult Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1991) and the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (Su et al., 2014) return more minor results. This sharply contrasts with the anecdotal evidence and feedback we receive. We suspect there are issues with measurement, which need to be addressed.

Nonetheless, four themes consistently emerge in the interviews and feedback we receive from participants who complete their trips (n=14 | 2017-2025): they have a greater sense of agency and see new pathways to a more hopeful future; they have significantly benefitted from mentoring and community with similar others; they intend to remain connected to others; they have set new outdoor adventure goals.

Testimonial: Raffaela Dragani (FND & Parkinson’s)

Raffaela has FND and Parkinson's and, early in her journey with us, struggled to walk from her car to her office. After 18 months of rehabilitation and mentoring support, alongside two friends, she successfully accomplished a long-held dream of completing a demanding, five-day tramp to Blue Lake Hut in Nelson Lakes National Park.

Reflecting on her trip (her ‘mission’) and her rehabilitation journey to get there, she says: “Hearing the story of others walking the same path and sharing their challenges with honesty was the most helpful part of my journey with Mastering Mountains.

“My mission confirmed how I can overcome my disability and work with it. It confirmed I can still do the things I love; I'm still me. I used to focus on everything I couldn’t do anymore. Now, I see what I can do. And that changes everything.

“I know that I have the tools to … manage [the physical challenges of FND]. I know that I can set goals. I know that I have wonderful things to aspire to, and I know there’s so much of life to live and be able to experience. You get to rewrite your story. Mine used to be about loss and limitation. Now, it’s about strength. Now, it’s about possibility.”

Testimonial: Steph Nierstenhoefer (MS)

Steph has multiple sclerosis and struggled to walk more than a couple of kilometres when she joined our programme. Earlier this year, after nine months of intensive rehabilitation and a year of mentoring, she successfully accomplished her goal of walking the Milford Track with her partner and their daughter over four days, a step toward their larger goal of completing all of New Zealand's Great Walks.

Reflecting on her rehabilitation journey, Steph writes: “The support from Mastering Mountains has been absolutely life-changing. The grant came at a time when I was feeling lost, unsure of how to move forward with my diagnosis. I was struggling to accept what MS meant for my future, but this support helped me shift my mindset.

“The support I received helped me accept my diagnosis, and connecting with others who understand MS made a huge difference. Knowing I’m not alone and that I can still adapt, explore, and embrace adventure has been truly life-changing. I’ve learned to accept support when I need it and to reach out to others with MS.

“I’ve realised that resilience isn’t about never struggling—it’s about finding ways to adapt, keep moving, and return to the things I love the most. The outdoors is still mine to explore, at my own pace, on my own terms. The future still holds adventure, just in a different way, and that’s okay.”

References

Abramson, A. (2024). Hope as the antidote. Monitor on Psychology, vol. 55 (1), p.88. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2024/01/trends-hope-greater-meaning-life

Ben Ezzdine, L., Dhahbi, W., Dergaa, I., Ceylan, H. İ., Guelmami, N., Ben Saad, H., Chamari, K., Stefanica, V., & El Omri, A. (2025). Physical activity and neuroplasticity in neurodegenerative disorders: a comprehensive review of exercise interventions, cognitive training, and AI applications. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2025.1502417

Berman, M. G., Cardenas-Iniguez, C., & Meidenbauer, K. L. (2021). An Environmental Neuroscience Perspective on the Benefits of Nature. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 61–88). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69020-5_4

Blythe, C. E. B., Nishio, H. H., Wright, A., Flores, P., Rand, K. L., & Naugle, K. M. (2025). Contributions of Hope in physical activity and exercise goal attainment in college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1499322

Burke, M., & Settles, B. (2011). Plugged in to the community. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communities and Technologies (pp. 1–10). C&T ’11: Communities and Technologies. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2103354.2103356

Colla, R., Williams, P., Oades, L. G., & Camacho-Morles, J. (2022). “A New Hope” for Positive Psychology: A Dynamic Systems Reconceptualization of Hope Theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809053

Dhand, A., Luke, D. A., Lang, C. E., & Lee, J.-M. (2016). Social networks and neurological illness. Nature Reviews Neurology, 12(10), 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2016.119

Duggleby, W., & Wright. K. (2009). Transforming Hope: How Elderly Palliative Patients Live with Hope. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive, 41(1), 204 –217.

Duggleby, W., Hicks, D., Nekolaichuk, C., Holtslander, L., Williams, A., Chambers, T., & Eby, J. (2012). Hope, older adults, and chronic illness: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(6), 1211–1223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05919.x

Duggleby, W., Ghosh, S., Cooper, D., & Dwernychuk, L. (2013). Hope in Newly Diagnosed Cancer Patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 46(5), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.12.004

Gladwell, V. F., Brown, D. K., Wood, C., Sandercock, G. R., & Barton, J. L. (2013). The great outdoors: how a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extreme Physiology & Medicine, 2, 1-7.

Hervás, G., & Vázquez, C. (2013). Construction and validation of a measure of integrative well-being in seven languages: The Pemberton Happiness Index. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-66

Hunter, M. R., Gillespie, B. W., & Chen, S. Y.-P. (2019). Urban Nature Experiences Reduce Stress in the Context of Daily Life Based on Salivary Biomarkers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00722

Irvine, K. N., Fisher, D., Marselle, M. R., Currie, M., Colley, K., & Warber, S. L. (2022). Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Qualitative Study on the Social Dimensions of Group Outdoor Health Walks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph1909535

Joel Botor, N. (2019). Hope Predicts Happiness with Life, Personal Well-Being, and Resilience Among Selected School-going Filipino Adolescents. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR), 47(2), 125–141. https://www.gssrr.org/index.php/JournalOfBasicAndApplied/article/view/10159

Joschko, L., Pálsdóttir, A. M., Grahn, P., & Hinse, M. (2023). Nature-Based Therapy in Individuals with Mental Health Disorders, with a Focus on Mental Well-Being and Connectedness to Nature—A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032167

Krokavcova, M., van Dijk, J. P., Nagyova, I., Rosenberger, J., Gavelova, M., Middel, B., Gdovinova, Z., & Groothoff, J. W. (2008). Social support as a predictor of perceived health status in patients with multiple sclerosis. Patient Education and Counseling, 73(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.019

Lee, B., Rumrill, P., & Tansey, T. N. (2022). Examining the Role of Resilience and Hope in Grit in Multiple Sclerosis. Frontiers in Neurology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.875133

Leite, A., Medeiros, A. G. A. P., Rolim, C., Pinheiro, K. S. C. B., Beilfuss, M., Leão, M., & Hartmann Junior, A. S. (2019). Hope theory and its relation to depression: a systematic review. Annals of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 2(2).

Long, K. N. G., Kim, E. S., Chen, Y., Wilson, M. F., Worthington Jr, E. L., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2020). The role of Hope in subsequent health and well-being for older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. Global Epidemiology, 2, 100018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloepi.2020.100018

Madan, S., & Pakenham, K. I. (2014). The Stress-Buffering Effects of Hope on Adjustment to Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(6), 877–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-013-9384-0

Motl, R. W., McAuley, E., Snook, E. M., & Gliottoni, R. C. (2008). Physical activity and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Intermediary roles of disability, fatigue, mood, pain, self-efficacy and social support. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 14(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500802241902

Murphy, E. R. (2023). Hope and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 50, 101558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101558

Ospina, J. P., Larson, A. G., Jalilianhasanpour, R., Williams, B., Diez, I., Dhand, A., Dickerson, B. C., & Perez, D. L. (2019). Individual differences in social network size linked to nucleus accumbens and hippocampal volumes in functional neurological disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 258, 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.061

Rommer, P. S., Sühnel, A., König, N., & Zettl, U.-K. (2016). Coping with multiple sclerosis-the role of social support. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 136(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12673

Schwartz, C., & Frohner, R. (2005). Contribution of Demographic, Medical, and Social Support Variables in Predicting the Mental Health Dimension of Quality of Life among People with Multiple Sclerosis. Health & Social Work, 30(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/30.3.203

Shanahan, D. F., Franco, L., Lin, B. B., Gaston, K. J., & Fuller, R. A. (2016). The Benefits of Natural Environments for Physical Activity. Sports Medicine, 46(7), 989–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0502-4

Shuda, Q., Bougoulias, M. E., & Kass, R. (2020). Effect of nature exposure on perceived and physiologic stress: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 53, 102514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102514

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

Snyder, C. R., Rand, K. L., & Sigmon, D. R. (2002). Hope theory. Handbook of Positive Psychology, pp. 257-276

Spytska, L. (2024). The Impact of Physical Activity on Brain Neuroplasticity, Cognitive Functions and Motor Skills. OBM Neurobiology, 08(02), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2402219

Soundy, A., Smith, B., Dawes, H., Pall, H., Gimbrere, K., & Ramsay, J. (2011). Patient’s expression of hope and illness narratives in three neurological conditions: a meta-ethnography. Health Psychology Review, 7(2), 177–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2011.56885

Steffen, L. E., Cheavens, J. S., Vowles, K. E., Gabbard, J., Nguyen, H., Gan, G. N., Edelman, M. J., & Smith, B. W. (2019). Hope-related goal cognitions and daily experiences of fatigue, pain, and functional concern among lung cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(2), 827–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04878-y

Su, R., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving [Dataset]. In PsycTESTS Dataset. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/t45315-000

Thoits, P. A. (1986). Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.416

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

Tonnesen, M., & Nielsen, C. V. (2024). Hope and Haunting Images: The Imaginary in Danish Parkinson’s Disease Rehabilitation. Medicine Anthropology Theory, 11(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.11.3.7486

Von Roenn, J. H., & von Gunten, C. F. (2003). Setting goals to maintain hope. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21(3), 570-574.

White, M. P., Alcock, I., Grellier, J., Wheeler, B. W., Hartig, T., Warber, S. L., Bone, A., Depledge, M. H., & Fleming, L. E. (2019). Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Scientific Reports, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44097-3

Wicks, C., Barton, J., Orbell, S., & Andrews, L. (2022). Psychological benefits of outdoor physical activity in natural versus urban environments: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of experimental studies. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 14(3), 1037–1061. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12353

Williams, F. (2017). The Nature Fix: Why nature makes us happier, healthier, and more creative. WW Norton